I know a lot of Al(l)isons. My wife is named Allison. My sister is named Alison. My friend Allison is named, well, Allison. My dad sometimes has to clarify which Al(l)ison he is talking about when he texts me. “Our Alison is getting ready for the new semester,” he’ll write to me every August as my sister prepares for a new school year. Other times, he’ll text a question: “How is Allison doing? Your Allison,” by which he also means our Allison, or our other Allison, his daughter-in-law, though it’s easy to tell the difference in print when we get the spellings right (one L versus two).

But this is not a story about those first two Al(l)isons, although my sister is a great lover of music (especially of U2 and James Taylor) and my wife is one of the most talented musicians I’ve ever had the chance to collaborate with (as one of my college bandmates once told me, always play with people who are better than you, and I’ve diligently followed that advice ever since). This is a rock and roll story about my friend with the same name as my sister and as my wife, an Allison who is one of the best guitar players I’ve learned from over the years. This is also a story about guitar pedals, so for those of you who are not musicians, or have only a passing interest in/knowledge of the little electronic devices we use to transform our electric guitar sounds into something otherworldly and strange, I should begin with a brief explanation of what these are and what they do:

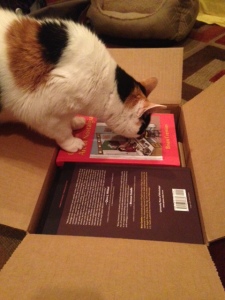

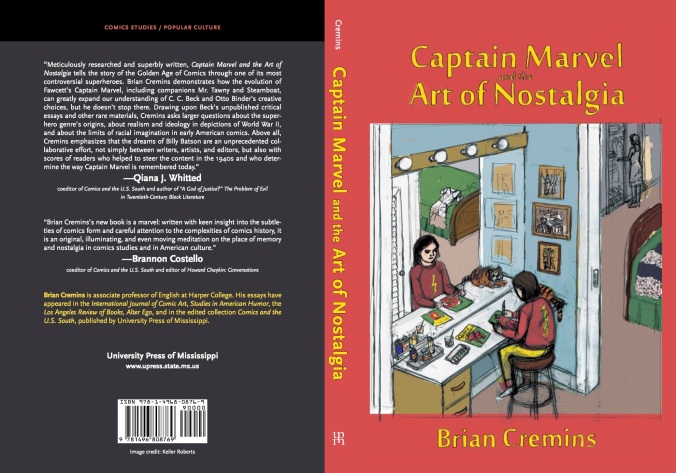

What you see in this photo are three sound processors for guitar—pedals, designed to be stepped on at gigs, in rehearsals, at recording sessions, in your basement or garage or living room or even on your back deck. Boss pedals—which have been manufactured by Roland, a Japanese music technology company, since the late 1970s—have a well-deserved reputation for being nearly indestructible. I’ve had the green one in the middle since 1992, the gray/silver one on the left since 1995, and the blue one on the right since 2008. Plug your guitar into them, then send a cable to an amplifier, and each box, colorful and easy to see on a dark stage, transforms the sound of your instrument in a different way.

The Blues Driver (BD-2) makes the guitar louder and more distorted, for example; it will not make you a blues master like B. B. King, Hound Dog Taylor, or Joanna Connor, but it will give you that overheated, piercing sound if you crank up the treble, close your eyes, and imagine you’re onstage at the Checkerboard Lounge or Rosa’s or Kingston Mines. In the middle, the green one—which has survived multiple beer spills and a long exile in my cousin’s basement (how it got there, I don’t remember, but he was kind enough to mail it back to me)—chops up your sound, almost like what a helicopter would sound like if you could plug your guitar into it (which sounds like fun, right?). You’ve heard this sound on a lot of recordings, especially ones from the 1960s, when tremolo was in vogue. Take a listen to Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Born on the Bayou” or to “Crimson and Clover” by Tommy James and the Shondells and you’ll know the sound instantly. It’s a warm, nostalgic pulse, an electronic heartbeat, the impossible sound of high school dances that probably were never that much fun in the first place, but sure seem that way when memory does its work. It’s amazing what a little green box like that can do.

The last one for me is the most special, since I’ve used it the most, from undergraduate voiceover recording sessions with actor David Harbour (long before he was David Harbour of Stranger Things and Black Widow, just another Dartmouth College undergrad, but a kind and tremendously talented one at that) to the stage at CBGBs to recent recording sessions in our living room. I think of the Boss RV-3 Reverb/Delay as the R2-D2 or C-3PO of my musical life, the little machine that’s been by my side for a very, very long time (I just used it to add a little echo when I was practicing this morning). Unlike the other two pedals, which I think of as the more grounded, earthy members of this little team, the RV-3, when turned up, will take you and your guitar into space, if space weren’t a silent vacuum. If you’re on your back deck but need your guitar to sound like you’re playing in a stadium—or maybe in the first rock and roll club on the moon—this is the pedal for you. And it’s the pedal for me too, I guess, since I’ve used it weekly since buying it at Manny’s Music on 48th Street during my spring break in March of ’95.

I got the idea to put these together on a little board like this from my friend Allison, another Boss player, who, when she was in her early 20s, toured and made a living in a wedding and party band. She and her bandmates—all young, talented women just like her—even managed at least one tour overseas. I was in my early 20s when I first met her and her husband Andy, the drummer in my band the Confessors. Not long after Andy and I started playing together in a power trio with our friend Tris on bass, I asked how he and Allison had met. He’d auditioned for her band, he said, not only because they were all phenomenal musicians, but also because he wanted to meet her. She looked cool. And she could play.

Having grown up mostly with other self-taught punk rock musicians, I discovered that Allison was a very different kind of musician, one unlike any other I’d met to that point (with the exception of my classically-trained friend and college bandmate Lawrence). She not only had a lot of technical skill but continued to learn and to develop her abilities by taking lessons with other highly trained musicians. For an inexperienced 22-year old like me, one who’d picked up the guitar age 16 and started playing in bands at 18, I didn’t understand why such a skilled, naturally gifted player needed to take more lessons. Today, after a few years of studying with Chicago jazz guitarist and master teacher John Moulder, I think I’m beginning to understand what Allison was searching for. But she got there long before I did.

By her early 30s, she was still playing, but also working full-time as a nurse and building a family with Andy and with their daughter. It’s only now, in my late 40s, that I understand the lessons she tried to teach me almost three decades ago. Watching her play her Telecaster through a 70s-era silverface Fender Twin (a very big, powerful, clean- sounding amplifier), I noticed she also had a board of six colorful Boss pedals on the floor, from an orange DS-1 (for more volume and distortion) to a pale blue Chorus, a sound that was essential for any working musician in the ’80s and early 1990s. You’ve heard that sound, too—just listen to Andy Summers on “Every Breath You Take.” One day at rehearsal, not long after visiting Andy and Allison for dinner and getting a chance to see and listen to Allison play guitar for the first time, I remember what Andy said: I told you she was really, really good. I nodded in agreement. I should have known. Her record collection was all Van Halen, Joni Mitchell, Led Zeppelin, James Taylor.

One of the best parts of being a musician is learning from the oral tradition that one player passes on to another, especially musicians in a small community like the one I was lucky to find myself in during the mid-1990s. Use heavier strings, my friend Lawrence advised me. You’ll get more distortion and feedback that way. Always tune up to pitch, never down, especially on a Gibson guitar, Tris told me. Also, he said, keep your eye on Andy’s right hand when he’s on the hi-hat or the ride. That’s your metronome. From Allison, not only did I learn about how to use effects pedals and processors in a subtle, musical way—like I said, I was self-taught, and at 22 I just wanted to play as loudly as possible—but I also learned, as the cliché goes, how to keep on learning.

What pick do you use? Allison asked. Usually a Fender medium, I said (a light, thin piece of plastic marbled to look like an old tortoise shell). Try one of these, she replied, handing me the green one you’ll see in this photo, a Dava Control Pick, designed to give a different feel, weight, and attack…depending on how you hold it:

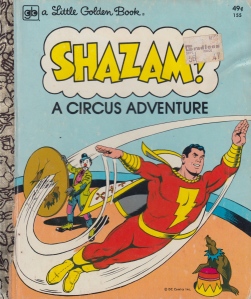

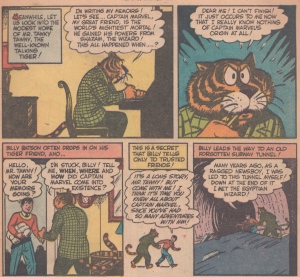

The idea that different guitar picks could create different sounds—especially when held carefully at different angles—was, as simple as it sounds, a life-changing moment for me. I was used to hitting the strings as hard as I could, as fast as I could, so that I wouldn’t lose my place in a song, or forget lyrics while I singing and playing at the same time. But suddenly I felt like Billy Batson meeting the wizard Shazam, or Arthur meeting Merlin and the Lady of the Lake for the first time. I didn’t even have to go to the local Daddy’s Junky Music to buy one of my own. Allison handed it to me. Just practice, she said.

The other picks in that photograph have stories, too, but I’ll save them for another time. After all these years, I’m still trying to master not only the instrument itself but also the amp and the pedals and that pick, which I’ve carried with me in a beat-up little Altoids tin since 1996. I’m still discovering new sounds with it, just like with those old Boss pedals. Some of those sounds come from technique, but others–the ones that mean the most–come from that room, and that little group of friends, and that jam session in the furnished basement of Andy and Allison’s home somewhere in Connecticut, sometime in the 1990s.